This week I was upset and ashamed by the events that unfolded in the covert screening of a care home in Essex. Footage showed care home staff roughly handling frail residents with dementia, laughing and mocking them, and ignoring repeated plaintive calls for help from a bedbound elderly woman.

In the fallout, there followed the usual responses: public outrage, pointed fingers and sackings, promises of “never again”, and calls to toughen up policing of standards. There was talk of installing CCTV in care homes to monitor care and provide an active deterrent to neglectful behaviour. The employer insisted was that these behaviours were carried out by a small number of staff and did not reflect the high standards within the care home.

I wanted to write because I am concerned by the way in which decisions on how to respond to care failings are made so rapidly and without in-depth analysis. The wholesale withdrawal of the Liverpool Care Pathway is another example of this – rather than explore the root causes and get creative in improving care in the last days of life, the entire care pathway was withdrawn. It also suggests that we are trying to shut the stable door a little late; a little like toughening knife crime sentences following the murder of a Leeds school teacher. Attempts to police and monitor the caring workforce are, in my opinion, ill-considered knee-jerk reactions, attempts at being seen to be doing something, without a robust evidence base. Such responses fail to focus on the root causes of such behaviours.

In addition, policing and punitive responses uphold and sustain a system in which care staff work in an environment characterized by fear of punishment and retribution. This is in addition to the stresses inherent in the nature of the work itself.

There are many explanations that have been put forward to account for the kinds of behaviours seen in this case, as in the case of the abuses at Winterbourne View and Stafford Hospital. These can be summarized as:

- “no time to care”

- “few bad apples”

- “poor management and leadership”

The “no time to care” argument is an important one. There is convincing evidence that poorly planned skill mix and task-driven routines are detrimental to the quality of care. However this does not explain why, even when staffing levels are dire, some individuals succeed in providing compassionate care.

The “few bad apples” argument does not offer a complete explanation either, although it is certainly understandable that care professionals who pride themselves on compassionate care seek to distance themselves. If this is the case, then the sheer number of instances of documented neglect and abuse illustrate that values-based recruitment either into education or employment are ineffective.

The “poor management and leadership” explanation offers important insight into how the culture of an organisation evolves and sustains itself. However the behaviours of individuals cannot entirely be justified by the way in which they are taught and led, otherwise all antisocial behaviour could be entirely explained environmentally, and in addition, one might expect to see all staff in such a situation behaving in a way which upholds these organisational values.

I don’t believe these three positions fully explore the complexities of recurrent examples of poor care, and that we need to engage in dialogue about two additional factors: ageism, and death anxiety.

200 years ago, life expectancy was around 40. Death occurred through infection, through accident, in childbirth, or through undiagnosed and mysterious illnesses. Over subsequent decades, accompanied by advanced in medicine, old age began to emerge as a source and cause of death in its own right – of course, there is always a diagnosis that finds its way on to the death certificate, but essentially the diseases that characterize old age are collectively defined by the wearing out of one organ or another, an atherosclerotic blood vessel here, or an atrophying brain there. Sherwin Nuland provides an illuminating account of these processes.

Thus, old age began to be associated with death and dying in and of itself. Perhaps as a consequence, Western culture places high value on youth, strength, vitality and beauty; one only needs to pick up any mainstream newspaper or magazine for proof of this. When coupled with visible evidence of bodily and cognitive changes, old age provides a potent reminder to us of our own mortality. Ageing shows us that our bodies and minds will deteriorate too, and that (unless we succumb to some other, premature death) our fate is also to sit helplessly as our bodily functions let us down. Evidence shows that older faces are rated as less physically attractive than younger ones, and that people with dementia trigger high levels of death anxiety.

Ageism is a direct consequences of the fact that elderly people represent our own future, they remind us that death, deterioration and loss of dignity are inevitable, unless we meet an earlier demise. This can be a source of profound anxiety, but one of which we may not be aware, at least not consciously. Reminders of death increase negative attitudes towards people who are perceived as different (see for example It has also been shown that exposure to disability, unpleasant body odours, and visible illness increase fear of death and the use of psychological defences. AI believe that ageism is therefore an important influence on the quality of care in settings such as care homes and one which has not entered the discussion much.

Martens et al (2005) suggest that elderly people symbolically represent a three-pronged threat to our immortality:-

- The threat of death – elderly people remind us that in one way or another we are all mortal.

- The threat of animality – when the body invariably deteriorates with advancing age, those body parts that we have managed to ignore, hide and deodourise for most of our lives make themselves very obvious. Incontinence, halitosis and flatulence trigger anxieties about our animal selves, they remind us that we are not really any different from other animals.

- The threat of insignificance – To buffer against death anxiety, people make efforts to boost their self-esteem. This is through identification with cultural values, which in our case include attributes like physical strength and beauty. The elderly present a symbolic loss of identity. If this is combined with cognitive impairment such as occurs in dementia, this loss of self can be deeply frightening.

Tom Kitwood’s revolutionary work on personhood in dementia identified ways in which many cultures, not just our own, have a tendency to depersonalize people with profound disabilities. He points out that the twin threats of losing ones cognitive abilities, combined with the painful evidence of the inevitability of death, lead to this “malignant social psychology”. If someone is denied their personhood, this action separates them from the other, and in doing so, the other is reassured that they are different and somehow immortal. It becomes much easier to treat that person in a way that is degrading or neglectful, often without awareness that one is doing so. I doubt that any of the carers filmed in the Panorama documentary would treat their own mothers or grandmothers in the ways in which they were shown treating residents.

To work in a care environment such as a nursing home is to be surrounded by reminders of mortality on a daily basis. I have met several healthcare professionals who deny that they are affected by the proximity of death in their daily work – “you get used to it”. When I was a new nursing student I recall a mentor telling me that I had better toughen up if I was going to “survive” nursing – I now realize she was essentially advising me to enlist the help of my defences so that I could cope with the level of suffering and sadness that I would witness.

The recommendations following the Francis inquiry into failings in Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust included the suggestion that all prospective nursing students work for a year as a healthcare support worker prior to commencing their training, in order to enhance their compassion. I believe this would be nothing but a highly effective way to ensure students are thoroughly conditioned into the culture of whichever ward they are assigned to, before even arriving at the University. In other words, unarmed with critical skills and theoretical background, learning will consist of conditioning and absorbing the values of the work placement. This is all well and good if the culture of the ward is one that is positive, that values personhood, that supports its staff and their contributions, that recognizes the stresses inherent in the job. If not, tough luck.

I do not believe that values-based recruitment is the panacea; nearly every prospective nursing student I have interviewed knows how to say the right things. Most of them mean it. But none of them are interviewed whilst tired, halfway through a long shift, face to face with a doubly incontinent patient who in their distress and disorientation is misinterpreting and physically resisting efforts to help, while a call bell from next door buzzes for the fourth time that hour. In difficult working conditions no amount of positive values can mitigate against the stresses that care workers are under.

Interventions to enhance compassionate practice such as education and values-based recruitment are important, but if these are delivered without attention to the impact of death anxiety then the issue is only partially solved. People with dementia who may not be able to control their bodily functions, communicate clearly, comply with required routines, or demonstrate socially acceptable behaviour, are vulnerable to the kinds of abuses that were highlighted in Bristol.

Organisations must acknowledge the impact of death anxiety on compassion in care of the frail and the dying. If they do not, staff may either become increasingly stressed until they experience burnout, compassion fatigue or rust-out. Alternatively, they recruit powerful psychological defences such as blocking, distancing and denial in order to defend themselves.

Death anxiety:- It is important that we become more able to acknowledge our fears of death, illness and dying since they contribute to the unconscious defences that appear to detract from the quality of caring for the frail. Specifically, interventions need to-

- Acknowledge individual vulnerability and fears around death and dying

- Engage leaders in developing compassionate care environments for staff as well as patients and residents

- Promoting activities to enhance self-compassion

- Promoting activities to enhance awareness and attention, such as mindfulness.

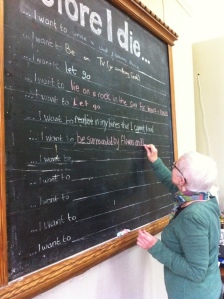

Cultural values – the second area to challenge is the set of cultural values from which ageism is born; if we can look at the values of youth, vigour, beauty and health as nothing more than efforts to preserve our mortality, then we might find we do not cling to them quite as strongly. Promoting images of beauty and vitality that do not adhere to the usual norms can be powerful (see here, here and here).

The discussions around care failings need to expand beyond politics to include consideration of cultural attitudes towards death and dying, philosophical issues around death anxiety, and contemplation of the impact of care work on the psychological and spiritual health of care workers. Tackling abuse means tackling ageism, which means challenging our cultural ideals and values, and acknowledging our fears of death and dying.

This is excellent and sensible speak – thanks for the article in e hospice.

Thanks. Very interesting.

An interesting article and one which highlights a dire need to do more to raise these unacceptable standards, instead of turning a blind eye.

Brilliant and thought provoking